In this Module, we will address the topic of gender-based violence (GBV), shedding light on the terminology, root causes and dynamics, as well as on concrete actions to prevent, identify and react in case it occurs. We will emphasize above all the need for you, as a young person, to be at the core of the discussion, engaging for collective actions and youth-led societal transformation, as GBV is not just a matter of adults’ lives!

Voices - Module 3

Introduction

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) refers to harmful acts directed at an individual based on their gender. It is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms. And they are at risk everywhere and anywhere — at work, at school, at home. According to the UN, GBVis a global public health emergency.

As we saw in module 2, following strict ideas about how boys, girls and other genders should act doesn’t just limit who we are and what we can do – it also creates a divide between genders based on what society thinks they should look like and how they should behave. This separation often leads to unequal power dynamics because society tends to prefer traits associated with guys, like being in charge and competing, over traits linked with girls, like being gentle and nurturing. Even though no one is purely “feminine”or “masculine”, we’re still taught to admire and strive for these ideal versions of being a boy or a girl. The problem is, these ideals are often unrealistic and even contradictory.

People who don’t fit into these traditional boxes, like guys who are seen as ‘soft’ or girls who have multiple partners, often face being left out, treated unfairly, or even bullied. This kind of mistreatment, based on someone’s gender or who they’re attracted to, is known as gender-based violence. Some people use this kind of violence to control others they see as less important or as a way to ‘punish’ those who don’t follow the typical rules of being a girl or a boy.

Try to think: what do you know about GBV? What do you hear from the media, and from people around you in general? Although we hear more and more talking about GBV, we can also observe that it is still treated as an “adults’ affair”. Instead young people suffer from GBV, as well as discrimination and abuse because of their gender, before the age of 18. We talk about teen dating violence (TDV) for indicating the specific type of GBV touching teenagers, and of school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) indicating what happens in schools on the matter. However, both phenomena remain largely under researched and under-addressed.

We said already that educating about the importance of sexual consent and desire is a fundamental aspect of respectful and healthy relationships, but it is also one crucial step towards eliminating GBV: consent education will equip you with a deep understanding of the significance of affirmative and ongoing consent, which is vital in reducing incidents of GBV and fostering positive, consensual relationships. Understanding desire on the other hand, helps individuals recognize signs of coercion and manipulation. When both partners understand and respect each other’s desires, it becomes easier to identify and resist coercive behaviours, thereby preventing instances of gender-based violence.

While prevention efforts are indispensable, it is equally important to create a supportive environment for victims or survivors of GBV, who may face various challenges, including re-traumatization when seeking assistance and justice. Here, peer support initiatives emerge as a beacon of hope and healing. Peer support systems provide victims or survivors with a safe space to share their experiences, seek guidance, and connect with others who have faced similar challenges. This sense of community and understanding is pivotal in helping victims or survivors regain their agency and self-esteem.

In order to begin addressing these issues effectively and sustainably, we will start from exploring the core concepts that make up a complete definition of GBV, to develop a basic understanding of all related issues. Before entering into this exploration, we recommend you to go through Module 2 of this Guide, and to review some key concepts, for instance the difference between “sex” and “gender” – do you remember?! We will then emphasise the need for collective action and peer support, for a safer and more equitable world for all.

Key Vocabulary and definitions

Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Gender-based violence refers to any type of harm that is perpetrated against a person or group of people because of their factual or perceived sex, gender, sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Gender-based violence is based on an imbalance of power. It is carried out with the intention to humiliate and make a person or group of people feel inferior and/ or subordinate. It can be sexual, physical, verbal, psychological (emotional), or socio-economic, among others.

In this guide we understand gender-based violence both comprising violence against women and violence against all genders. – Council of Europe

Teen Dating Violence (TDV)

Teen dating violence — also called intimate relationship violence or intimate partner violence among adolescents or adolescent relationship abuse — includes physical, psychological or sexual abuse; harassment; or stalking of any person ages 12 to 18 in the context of a past or present romantic or consensual relationship. – National Institute of Justice

School related gender-based violence (SRGBV)

SRGBV can be defined as acts or threats of sexual, physical or psychological violence occurring in and around schools, perpetrated as a result of gender norms and stereotypes, and enforced by unequal power dynamics. – Unicef

Sexual Consent

Sexual consent is an agreement to participate in a sexual activity. It should be freely given, reversible, informed, enthusiastic and specific. – Planned Parenthood

Victim/Survivor of GBV

A person who has experienced gender-based violence may be referred to as a victim or survivor. The term victim has been subject to criticism and often replaced by the word survivor which emphsizes the agency of the people who have experienced GBV. In this guide we use both terms because people affected by gender based violence may identify with one or the other based on their own experience.

Rape

Any non-consensual vaginal, anal or oral penetration of the body of another person where the penetration is of a sexual nature, with any bodily part or with an object, as well as any other non-consensual acts of a sexual nature by the use of coercion, violence, threats, duress, ruse, surprise or other means, regardless of the perpetrator’s relationship to the victim. Causing another person to engage in non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with a third person is also considered as rape. – EIGE

Catcalling

Vulgar sexual comments made on the street.

Femicide

The term femicide means the killing of women and girls on account of their gender, perpetrated or tolerated by both private and public actors. It covers, inter alia, the murder of a woman as a result of intimate partner violence (IPV), the torture and misogynistic slaying of women, the killing of women and girls in the name of so-called honour and other harmful practice-related killings, the targeted killing of women and girls in the context of armed conflict, and cases of femicide connected with gangs, organised crime, drug dealers and trafficking in women and girls. – EIGE

Abuse of power

A misuse of power by someone in a position of authority who can use the leverage they have to oppress persons in an inferior position or to induce them to commit a wrongful act. – The Law Dictionary

Gender inequality

Legal, social and cultural situation in which sex and/or gender determine different rights and dignity for women and men, which are reflected in their unequal access to or enjoyment of rights, as well as the assumption of stereotyped social and cultural roles. – EIGE

Heteronormativity

Heteronormativity is what makes heterosexuality seem coherent, natural and privileged. It involves the assumption that everyone is ‘naturally’ heterosexual, and that heterosexuality is an ideal, superior to homosexuality or bisexuality. – EIGE

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence between current or former spouses as well as current or former partners. It constitutes a form of violence which affects women disproportionately and which is therefore distinctly gendered. – EIGE

Domestic Violence

All acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit, irrespective of biological or legal family ties, or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence as the victim. – EIGE

Toxic Masculinity

Toxic masculinity is an attitude or set of social guidelines stereotypically associated with manliness that often have a negative impact on men, women, and society in general.

– Vallie S. 2022

Dating and online dating

Dating is spending time together to explore romantic or sexual connections and look for potential partners, white online dating is doing the same thing but using the internet for communication.

Let’s talk about consent

We see the concept of consent as the starting point of the discourse over GBV.

Consent is the voluntary and informed agreement given by all parties involved in a sexual activity. It should be continuous, enthusiastic, and can be withdrawn at any time without consequences. This means that before starting any practice with someone, you need to know if the person wants that too. Consent is the willingness of being together, it is the meeting point of common desires. It is a matter of personal boundaries, and respect of the boundaries of others; of knowing themselves and their desires, and being able to communicate them; of checking in if things aren’t clear; of responsibility, for asking it or giving it.

Watch this video to understand better what we mean by consent:

Sexual activity without consent is violence

If we stop and analyze the term, we will notice that the word itself isn’t enough to help us understand the complexity of what it means. For instance, a person could feel ashamed, fearful or lack the tools to say “no”. Despite the fact that the person is explicitly and verbally saying “yes”, that “yes” may not be free, or informed.

“Consent implies that you have to be sure to also go against that person and say no.”

“I was afraid of maybe not being enough for that person, or of disappointing them in some way and so I often felt kind of uncomfortable because I didn’t really want to and this person made me feel very uncomfortable.”

This video shows the complexity of this concept by using the acronym of FRIES:

Consent is FRIES:

- Freely given. Consenting is a choice you make without pressure, manipulation, or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

- Reversible. Anyone can change their mind about what they feel like doing, anytime. Even if you’ve done it before, and even if you’re both naked in bed.

- Informed. You can only consent to something if you have the full story. For example, if someone says they’ll use a condom and then they don’t, there isn’t full consent.

- Enthusiastic. When it comes to sex, you should only do stuff you WANT to do, not things that you feel you’re expected to do.

- Specific. Saying yes to one thing (like going to the bedroom to make out) doesn’t mean you’ve said yes to others (like having sex).

ASKING FOR CONSENT

“Can I…? Do you want me to…?” Easy, important questions, and a lot of possible answers, both verbal and nonverbal. But only an explicit and enthusiastic YES is consent. Silence is not consent. Expressions of doubts neither. And this applies not only to the very first time you’re with someone: even if you had sex before, or you are with the person(s) for a long time, you still need to ask for consent, every time. Never, ever pressure your partner into something they don’t want to do or seem unsure about. Let them know it’s okay if they want to stop or do something different. And once you know someone isn’t into what you’re asking, stop asking. Everyone deserves to have their boundaries respected. Being pressured into doing sexual acts doesn’t feel good, and it can ruin a relationship.

GIVING CONSENT

Your body is yours and you only get the final say over it: even if you agreed on something earlier, if you changed your mind, if you have new doubts. You can say “no” at any time, and your partner needs to respect that. Don’t feel bad to express your feelings and emotions.

Consent is also about laws: there are laws, in every country, defining who can consent and who can’t: people who are drunk, high or passed out cannot consent to sex. Also, there are laws that protect minors (people under the age of 18) from being pressured into sex with someone much older than them. We talk about “age of sexual consent” to indicate how old a person needs to be in order to be considered legally capable of consenting to sex – under this age, adults involved face jail time and being registered as a sex offender. The age of consent varies from country to country:

|

Italy |

Spain |

France |

Greece |

Cyprus |

Belgium |

Lithuania |

|

14 |

16 |

15 |

15 |

17 |

16 |

16 |

In our culture, the practice of consent is not very “natural”, because of its correlation with patriarchy and gender imbalances in which we live, because of the concept of power and the attitude to be performative, and competitive: it may be difficult to accept “no” as answers (see module 2 to learn more about gender imbalances). The path for building a different society, based on a culture of consent, is still long and difficult. But it starts from the commitment to be part of this change and approaching it with a transfeminist set up will improve its development.

Feminism is a social and political movement advocating for the equal rights, opportunities, and treatment of all genders. It challenges and seeks to dismantle systemic gender-based inequalities, discrimination, and stereotypes. That’s why we also talk about transfeminism, which refers to a specific subset of feminism that focuses on the rights and experiences of transgender individuals within the broader feminist framework. It addresses the intersectionality of gender identity and feminism, working towards inclusivity and equality for all women, cis and trans* (see module 2). Transfeminism challenges traditional gender norms, promotes inclusivity, and addresses the specific vulnerabilities and discrimination, contributing to a more comprehensive and effective fight against all forms of gender-based violence.

Watch out this video on the importance of consent.

“There was this time, as a young adult in a relationship with an unstable person, when I felt in danger and felt that the only choice for my safety was to agree to a relationship to calm the violence.”

“It’s just a joke”: Consent Culture vs Rape Culture

What obstacles the culture of consent to be spread in our society is the persistence of its antagonist, rape culture. This concept describes a society that encourages, normalizes and rationalizes gender-based violence, and above all sexual violence, as inevitable and a part of “natural” human behavior, rather than understanding it as structurally and culturally created and sustained. Social problems like sexist attitudes and gendered stereotypes can all lead to gendered violence. Small things like pulling a friend up on a sexist joke can help. It might be uncomfortable at first, but letting the people around you know that you don’t support those kinds of behaviours can make them stop and think twice about what they’re doing.

The best instrument we suggest to learn more and deeply understand GBV is the Rape Culture Pyramid: it shows how sexist attitudes can lead to escalating levels of abuse, how behaviors, beliefs, and systems are built on and work in conjunction with one another. At the bottom of the pyramid there are more common forms of violence such as sexsist jokes and attitudes or catcalling. These are often not even seen as forms of violence but they are nonetheless, and they form the basis for more dangerous forms including femicide. This pyramid only shows some examples of violence – the list is not exhaustive – but allows us to see that the change starts from the bottom of the pyramid. If we don’t understand and eliminate smaller forms of violence we cannot understand and eliminate the bigger ones.

What is the role of the media in how we talk about GBV?

Have you ever thought about how popular culture and media impact and shape our attitudes towards sexuality, sometimes reinforcing social norms and common beliefs, including the most violent ones? Mainstream media play a very important role in the perpetration of rape culture. Here are some examples of how this is done:

Towards the perpetrator:

- The media tend to depict rapists or people who have committed femicide as beasts or sick people, someone that is easily identifiable and distinguishable from the people we normally meet in our daily life; or a very ordinary person who was suddenly struck by a rapture and lost his mind. In reality we know that the vast majority of gender based violence episodes are committed by someone that the victim or survivor knew well, such as the (ex) partner, a relative or a friend.

Towards the victim or survivor:

- The media tend to further blame the victim or survivor of GBV by insinuating that they are in some ways also partly responsible for the violent behavior. What were they wearing? Were they drunk? Did she make them believe she actually wanted it? Are they lying? and so on. This is called victim-blaming. In reality, the only person responsible for a violence is the person who commits it.

The further up we go, the less socially acceptable the behaviours are. But we can’t measure harm to a victim or survivor by what ‘category’ it falls into – apart from death, right at the top. Everyone’s experience is different.

The tree of gender-based violence

Understanding the multifaceted nature of GBV is crucial in addressing this pressing concern. In order to talk about it, we like to represent it with the image of the tree:

Roots – Root causes

The roots are the root causes of GBV: GBV happens because of a society’s attitudes towards and practices of gender discrimination. Typically, genders are put in rigid roles and positions of power, often with people socialized as women and other genders in a subordinate position in relation to men. This “accepted” gender roles strengthen the assumption that men have decision-making power and control over the rest of people. Acting GBV, perpetrators (whoever they are) seek to maintain privileges, power and control. Additionally to this, we mention also among the root causes the fact that in contexts of lack of awareness about human rights, gender equality, democracy and non-violent means of resolving problems, can be strengthened.

Root causes include:

- abuse of power

- gender inequality

- patriarchy

- heteronormativity

- gender binary

Weather / Temperature – Contributing factors

Sun, rain, clouds represent the “climate” in which the tree may grow bigger and stronger. They represent all the so-called “contributing factors”: while gender inequality and abuse of power are the root causes of all forms of GBV, various other factors may influence the type and extent of it , increasing ones’ vulnerability to GBV. Contributing factors are often mistaken as causes but it’s important to distinguish between them in order to fight against GBV.

Contributing factors include:

- abuse of substances;

- economic inequalities

- lack of education;

- lack of social support, from institutions, families for example.

Branches – Type of GBV

The trunk and branches of the tree represent the different types of GBV that can occur. They can be grouped under four general categories (emotional or psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, economic abuse), that climb up to become the branches of the tree. In the images, we have represented the most occurring among adolescents.

Types of GBV include:

- Psychological violence, which causes psychological harm. It includes bullying, harassment, stalking, control, coercion, isolation, verbal insult and more.

- Physical violence, which causes harm and uses physical force. it includes beating, kicking, punching and more.

- Sexual violence, which refers to sexual acts performed without the other persons’ consent. It includes rape, assault, trafficking of human beings, unwanted sexual verbal conduct and more.

- Economic violence, which refers to acts that cause economic harm. It includes restricting financial resources, property damage, deprivation, limitation to employment and more.

Leaves – Consequences of GBV

The leaves are the consequences of GBV for victims or survivors and their surroundings, and are far reaching: from the physical consequences to emotional and psychological consequences.

Consequences of GBV include:

- Psychological consequences: feeling ashamed, anxious, depressed, loss of appetite,difficulty to attend school or study and more

- Physical consequences: health problems, self-harm, STIs, unwanted pregnancies and more.

- Functional: changing a route or taking down a profile.

- Social consequence: exclusion, rejection or isolation by family, friends.

Who is affected by GBV?

Now that we have looked in depth at the definition of GBV, let’s focus for a while at who is the most affected, always keeping in mind that usually we only know the number of individuals who report GBV, not all of the individuals who have experienced GBV (there are a lot of reasons why this happens, like cultural factors, stigma or fear).

“Sometimes, it has happened to me in the past, to continue a sexual encounter that I did not really feel like having, in order to please my partner. Also when I was young, I felt someone intentionally and sexually rubbing my leg on the bus and I took away my space. Most of the time, I didn’t say anything because of embarrassment. Other times, I would get up and leave the seat.”

We said already that GBV affects people of all ages and all genders, because of their gender, and that’s exactly why we use the more complete expression “gender-based violence”. However, people socialized as women and girls are worldwide the most affected. One out of three has experienced GBV during their lifetime (WHO, 2021). The main form of violence affecting women is intimate partner violence (IPV). Young women aged 15 to 19 are more at risk of IPV than adult women: by the time they are 19 years old, almost 1 in 4 adolescent girls (24%) who have been in a relationship have already been physically, sexually, or psychologically abused by a partner (WHO, 2021).

The LGBTQIA+ community faces heightened violence from peers, from families that might apply pressure on the individual to conform to traditional gender roles, from strangers being just homo-lesbo-bi-transphobic. Most LGBTQIA+ students report having experienced bullying or violence on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression (Plan/ICRW, 2015), as young people who are perceived as “resisting”, or as not fitting into traditional or binary gender norms, are at high risk of violence. Watch this video about GBV, youth and the LGBTQIA+ community.

You may have also heard the term toxic masculinity which refers to the fact that these social norms associated with men often impact negatively on men themselves and on other genders. It’s not to say that masculinity is bad, but that there are some behaviors connected to masculinity (such as being tough for example) that may have a negative impact (see module 2 to learn more about gender expectations).

“Dear diary, today again I was insulted and isolated for my sexual orientation. I wonder what is wrong with the LGBTQIA+ community. What is wrong with someone being part of it or me being bisexual?”

The “man box” – Especially in the school environment, boys are still expected to behave ‘like a man’, regarding their emotions, way of being and act, thus to be aligned to the “normative” definition of masculinity. We call it “the man box” to indicate the set of expectations according to which “a real man” should live – Watch out this video!

You may have also heard the term toxic masculinity which refers to the fact that these social norms associated with men often impact negatively on men themselves and on other genders. It’s not to say that masculinity is bad, but that there are some behaviors connected to masculinity (such as being tough for example) that may have a negative impact (see module 2 to learn more about gender expectations).

#NotAllMen – On the other hand, it happens more and more often, especially on social media and when severe cases of GBV are medialised, that we come across this hashtag. With this expression, people tend to claim a sense of injustice directed towards people socialised as men: “It is not a systemic problem, not all men are rapists nor murderers!”. Well, pointing this out is often seen as a rejection of responsibility towards other genders who, as we are seeing in this section, are much keener to be affected by GBV because they are less privileged in society.

Understanding gender-based violence is crucial, especially when it comes to girls, young women, and young trans individuals who face more than one type of inequality or discrimination. When different forms of unfair treatment overlap, it increases the chances of experiencing gender-based violence. For instance, Black or Minority Ethnic (BME) girls might face gender-based violence intertwined with racism and sexism, while violence against girls with diverse abilities could involve disablist abuse along with sexism. These groups may find it harder to get support, and the impact of the violence they experience may be even greater.

We call this approach ‘intersectional’ because it considers how violence happens at the crossroads of different types of inequality or discrimination. This means looking at how different factors, like race, disability, or gender, all come together to affect someone’s experience of violence and their ability to get help. This is called intersectionality. To learn more about it go to module 5.

How can I identify GBV in my relationships?

In module 1, we have already explored the different ways to build, and recognise, safe and healthy relationships. At this point of our journey, it is now time to talk about unhealthy ones – being the ones which lack the different characteristics expressed already, and may worryingly become what is called Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), Teen Dating Violence (TDV) or Domestic Violence,which refers to violent behaviour occurring within households or family environments.

Watch out this video on intimate partner violence!

Terms like GBV (Gender-Based Violence) or IPV (Intimate Partner Violence) are often considered more inclusive and encompassing compared to the term “domestic violence.” GBV and IPV highlight the broader context and diverse forms of violence experienced beyond the traditional domestic setting, recognizing that violence can occur in various relationships and societal structures. The use of the term GBV acknowledges that violence isn’t confined solely to intimate partner relationships or within the household but extends to broader societal issues rooted in gender inequality, power dynamics, and discrimination. It encompasses violence that may occur in public spaces, workplaces, or within communities based on an individual’s gender identity. In contrast, the term “domestic violence” historically focused mainly on violence within familial or household settings, potentially excluding other forms of violence, such as violence against women in public spaces or structural inequalities that perpetuate violence. Emphasising GBV or IPV recognizes the need for comprehensive approaches that address societal attitudes, legal frameworks, and institutional changes to combat violence against individuals based on their gender, orientation, or identity. It acknowledges that violence isn’t confined to a single space but is a multifaceted issue requiring a holistic response.

What are the signs of a toxic relationship? Watch out this video!

It’s hard sometimes to recognize the signs of unhealthy or abusive relationships – some of the clearer signs are:

- Control, when one takes all the decisions and tells the other on what to do, what to wear, or whom to associate with, or tries to isolate them.

- Dependence: when one is afraid of the consequences of breaking up the relationship and thinks that they cannot exist without the other person.

- Digital control, when one keeps track of the other person through social media or digital platforms; or when they send constant messages demanding the other person’s attention at all times.

- Dishonesty, when one keeps information from the other or manipulates them

- Disrespect: when one shames, mocks or gossips about the other behind their back.

- Hostility, when one person creates conflicts with the other or avoids solving them in a respectful way.

- Harassment, when one makes the other feel unsafe through behaviors like catcalling or inappropriate comments about the other’s body or behavior.

- Intimidation, when one person tries to make the other feel small and fearful, using tactics such as isolating them from friends and family or threatening violence or a breakup.

- Physical violence, when one uses physical force on the other.

- Sexual violence, when one person enacts sexual activity on the other without their consent.

These behaviours may apply to all kinds of relationships, not only to romantic and sexual relationships but also friendships, family relationships, casual relationships, work relationships and many more.

Unhealthy behaviours can happen sometimes, but what happens very often is that people in unhealthy relationships don’t try to change or learn from those abusive behaviours. So, it is very possible that unhealthy relationships can turn into abusive relationships.

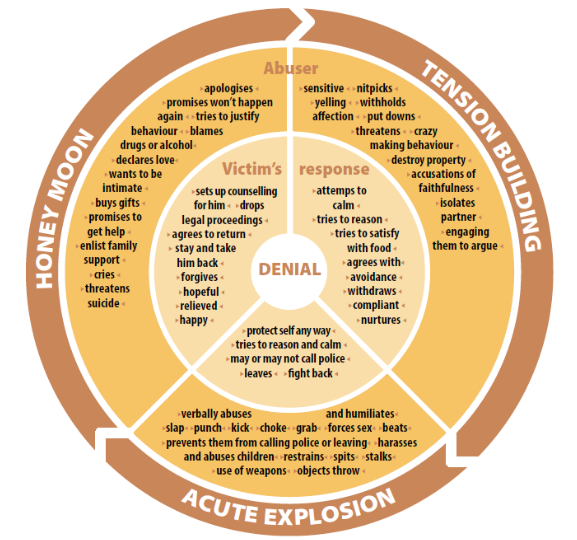

One further reason why people stay in abusive relationships can be understood through the so-called Cycle of Violence, in which the abusive behaviour aims to keep the abused person in the relationship through promises and denials.

Infographic by Council of Europe

The so-called honeymoon is when the abuser in an unhealthy relationship acts a sudden positive change that may seem very similar to the early part of the relationship, while apologising, promising to change and offering presents. However, soon the tension raises again and the old power structure is reasserted, eventually also the episodes of violence, until becoming closer and closer to each other and enter in an acute explosion. In this situation, typically the victim or survivor doesn’t initially recognise the cycle, while the abuser is denying responsibility.

Is Your Relationship Healthy?

Find out now with our quick and easy quiz. Discover the strengths of your relationship and areas for improvement.

How does GBV happen online? Online GBV

Another situation on which we want you to be aware of is the occurrence of GBV in the online space. Nowadays, more and more people meet online, through dating apps and social media. Online dating and sexting (sharing sexually explicit content through chats) have become two very common ways for young people to make new connections and explore desires. They can be a great way to express your sexuality and foster intimacy, if based on mutual respect and consent. At the same time it’s important to pay attention to some security issues in order to stay safe.

Online Gender-Based Violence can take many forms:

- Cyberflashing: sending explicit images without the receivers’ consent

- Cyberstalking: using digital tools to surveil the other person (reading messages or monitoring their movements)

- Digital voyeurism: recording, filming, viewing and sharing online videos or images without their consent (e.g. through hidden cameras, deepfaking or stealing of photographs).

- Doxing: sharing personal data and inciting others to contact the targeted person

- Identity theft and fake profiles: pretending to be someone else to harm the other person.

- Gender-based hate speech: shaming, insulting, making hurtful comments to the other person based on their gender identity or orientation.

- Morphing: creating and sharing deep fakes of the other person to sexualise them.

- Online grooming: establishing a relationship online with sexual aims.

- Online sexual harassment and bullying: bullying through online platforms (video)

- Non -consensual dissemination of intimate photos: sharing intimate photos of someone without their consent

- Sexploitation: commercial exploitation of sexual material

- Online threats and black mailing: threatening to disclose personal images or information unless some demands are met. when these demands are sexual it’s called sextortion.

- Zoom bombing when people join online groups or chats and post racist, sexist or other content to disturb the participants.

Online GBV has very harmful consequences on the victim or survivor, as explained earlier for GBV: physical, psychological, emotional and economic consequences.

“When I was younger, we used to argue with my parents, maybe there was a bit of a lack of love, I wanted a lot of attention, and I got it online. And that was not a good choice. I “fell” into the internet at a very early age, I saw a lot of things there that a kid should not see, and I encountered older people, it was very very wrong and I was one of those people who fell into that trap…and there were pictures… and other bad stuff.

“A friend from the school created a gmail chat on the school account and added several girls in a group called “the pretties” and asked us for pictures wearing only bra and knickers. None of us sent them and the school staff spoke to him and I was asked to show the chat. I don’t know what the school did.”

Love is not controlling! Watch out this video.

Online violence, just as all violence is never the victim or survivor’s fault and can happen to anyone. While it’s a systemic issue, there are some tips you could follow to minimise the possibilities:

- Update your passwords every once in a while, and keep them safe. You can also use security mechanisms to like anti-virus programs.

- Avoid keeping your webcam open in your private spaces to avoid collection of private images in case of hacking.

- When meeting people online, pay attention to: profiles without pictures or with pictures that look fake; profiles without information in the bio; people who refuse to talk through the phone or video call; people who ask you for money.

How to identify, handle and report situations of GBV

“I have experienced sexual harassment in the subway and in nightclubs when strangers touched my ass or breasts. In the different situations I reacted in the same way because there was this group of men, in which one touches you and when you turn around, you don’t know who was and everyone is laughing, so I decided to insult them and leave and tell my friends, but we did nothing else for fear of confronting them.”

GBV could happen everywhere, from schools to social hangouts, from unwanted comments to actions that make people uncomfortable. It is important to learn to navigate through such situations since it creates a bad atmosphere and takes away our right to feel safe and respected. Education and awareness are super important in fighting against this problem and making sure everyone is treated fairly!

The steps mentioned below can be helpful for someone to identify and eventually handle situations of GBV:

- Do not blame yourself: it’s never your fault. The perpetrator is the only one who has taken the decision to harm you, and GBV can happen to anyone even if you take precautions.

- Recognize the behavior: Confirm that the behavior you are encountering is GBV. It can take many different forms, such as unwanted advances, remarks, or any other sexual conduct that makes you uncomfortable – the ones explained above.

- Keep track and evidence of the incidents: Note down the incidents’ dates, times, locations, and specifics by keeping a record of them. Keep a record of all communications about the harassment. If you ultimately decide to report the harassment, this paperwork may be essential! If it’s online violence, keep all the evidence you have.

- Set boundaries: Express your displeasure to the harasser in a firm and clear manner. Tell them clearly and firmly that their behavior is unwanted and that you want it to stop. Setting limits might help those who don’t always know their acts are wrong by bringing their attention to them. If it’s online violence consider blocking the perpetrator.

- Know Your Rights: Become familiar with the laws and guidelines concerning GBV happening in school and in your community. Knowing your rights will give you more control over the situation.

- Consider Legal Advice: think about getting legal advice from a lawyer. If necessary, they can advise you on your legal choices and assist you in taking the proper legal action.

- Self-Care and psychological support: Remember to prioritize your well-being. Dealing with GBV can be emotionally draining. Engage in self-care activities that help you relax and cope with stress, such as talking to a counselor or therapist.

- Stay Persistent: Don’t be discouraged if the process takes time. Stay persistent and assertive in your pursuit of resolution. Your right to a safe and respectful environment is fundamental, and taking action is crucial in ensuring your well-being.

- Report the incident and seek support: some people may be hesitant to report to the authorities for fear of escalation or for fear of not being taken seriously. This is unfortunately still often a reality and for this reason it’s important that you do what you feel comfortable with, without any pressure. These are some options:

- You can talk to your family members or friends who may offer initial support

- You can also talk to your teachers and school if you feel comfortable: they should be able to take the necessary measures and refer to internal policies for Child Protection.

- If the incident is happening online, you can report the improper content to the platform administration.

- You can look out for NGOs or hotlines in your city or country

- You can report to the police

If you are not the person experiencing GBV but there is a disclosure in your group of friends here are some tips you can follow:

- Don’t ignore what they’re saying

- Let them know that you believe them

- Let them talk as much as they want, without insisting for them to tell more

- Consider with them the possibility of talking to other people keeping in mind that the priority is always their comfort

- Value their choice to share this with you and thank them

- Let them know that they are not alone and other people are in similar situations

- Let them know that it’s not their fault

- Pay attention to their questions and ask them how they would like to act, rather than prioritising your own advice.

- Listen closely to your own feelings too and make sure that you are in the right mental place to engage with the situation.

References

Abuse of power (n.d). The law dictionary. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://web.archive.org/web/20201112033832/https://dictionary.thelaw.com/abuse-of-power/

Armelli, P. (2021). Rape culture, perché è importante capire che cos’è la cultura dello stupro. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://www.wired.it/attualita/media/2021/04/21/rape-culture-cultura-dello-stupro-cos-e/

EIGE (2023) Forms of violence, European Institute for Gender Equality. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/what-is-gender-based-violence/forms-of-violence

EIGE. (2023). Glossary & thesaurus. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/overview

Gender inequality. European institute for gender equality. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/terms/1329?language_content_entity=en

Global guidance on addressing school-related gender-based violence (n.d). Unicef. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://www.unicef.org/documents/global-guidance-addressing-school-related-gender-based-violence

Glossary & Thesaurus. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/overview

Intimate partner violence. European institute for gender equality. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/terms/1198?language_content_entity=en

Lesta, S., Pana A. (2012). A Manual for empowering young people in preventing gender-based violence through Peer Education. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://medinstgenderstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Y4Y-Manual_digital_v12.pdf

Planned Parenthood. (n.d.). Official site. Retrieved from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/

Rape. European institute for gender equality. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/terms/1199

Sexual consent (n.d). Planned parenthood. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/relationships/sexual-consent

Teen dating violence (n.d). National Institute of justice. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/crimes/teen-dating-violence

UN Foundation. (2022). Stand with her: 6 women-led organizations tackling gender-based violence. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/stand-with-her-6-women-led-organizations-tackling-gender-based-violence/?gclid=CjwKCAjws9ipBhB1EiwAccEi1NaZUAMuA3J3nUnP09G3n3AUrmBTqOl-xYDPvhDXzWS0S3lFRu0uTBoC4EoQAvD_BwE

UN Women. (2015). A Framework to underpin action to prevent violence against women. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/11/prevention-framework#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20that%20approximately,be%20addressed%20in%20our%20time

UN Women. (2021). Youth Toolkit. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/Youth-Toolkit_14-Dec_compressed-final.pdf

UNFPA. (n.d.). Managing Gender-based Violence Programmes in Emergencies. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/GBV%20E-Learning%20Companion%20Guide_ENGLISH.pdf

UNICEF. (n.d.). Global guidance on addressing school-related gender-based violence. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://www.unicef.org/documents/global-guidance-addressing-school-related-gender-based-violence

Vallie S. (2022). What is toxic masculinity?. Webdm. Retrieved 5 February 2024 from https://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/what-is-toxic-masculinity

Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance. (n.d.). Ending Rape Culture Activity Zine. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://www.communitysolutionsva.org/files/Rape_Culture_Pyramid_discussion_guide.pdf

What is gender-based violence? (n.d). Council of Europe. Retrieved 5 February 2023 from https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/what-is-gender-based-violence

WorldBank. (2022). Violence against women and girls – what the data tell us. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/overview-of-gender-based-violence/

Youth.gov. (n.d.). Characteristics of healthy & unhealthy relationships. Last retrieved 4 February 2024 from https://youth.gov/youth-topics/teen-dating-violence/characteristics